FORCED DISPLACEMENT

Finding 1: Prolonged vulnerability

The overwhelming majority of displaced populations continue to be vulnerable to disasters and conflict years after their initial displacement.

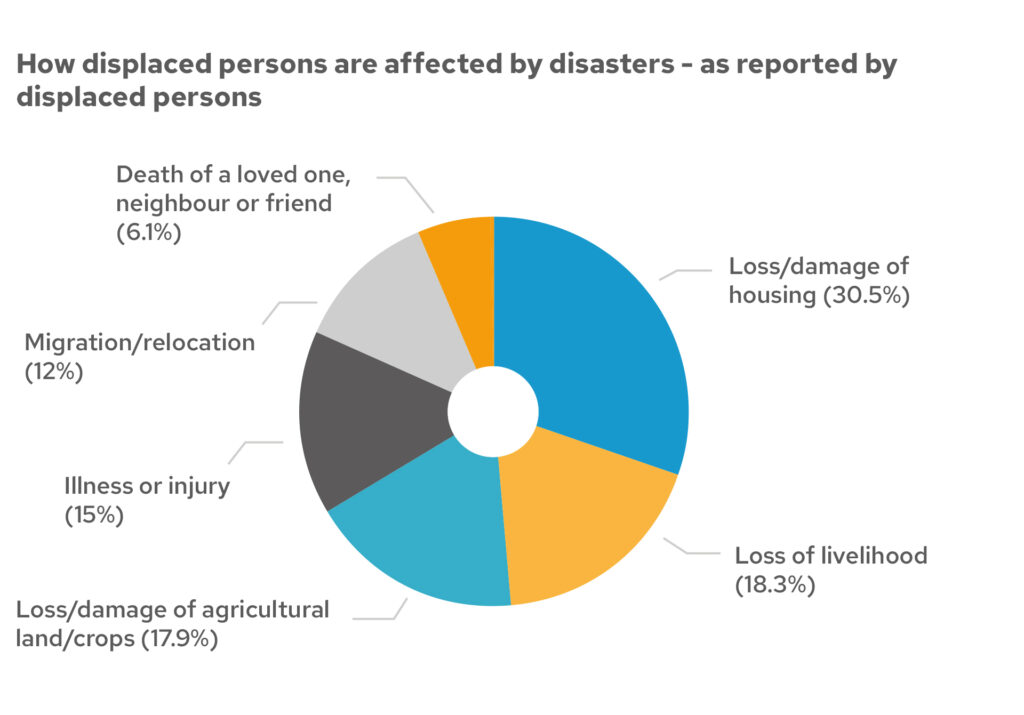

Two-thirds of those interviewed stated that they continue to be affected by disasters. They continue to face ongoing hazards – especially in the immediate years after leaving their home. Those displaced less than three years perceive consequences of the risks they face to be flooding, economic and livelihood loss, and shelter destruction. The biggest loss to them in these ‘new’ disasters was said to be through loss/damage of housing and the loss of livelihood.

Mapping displaced persons

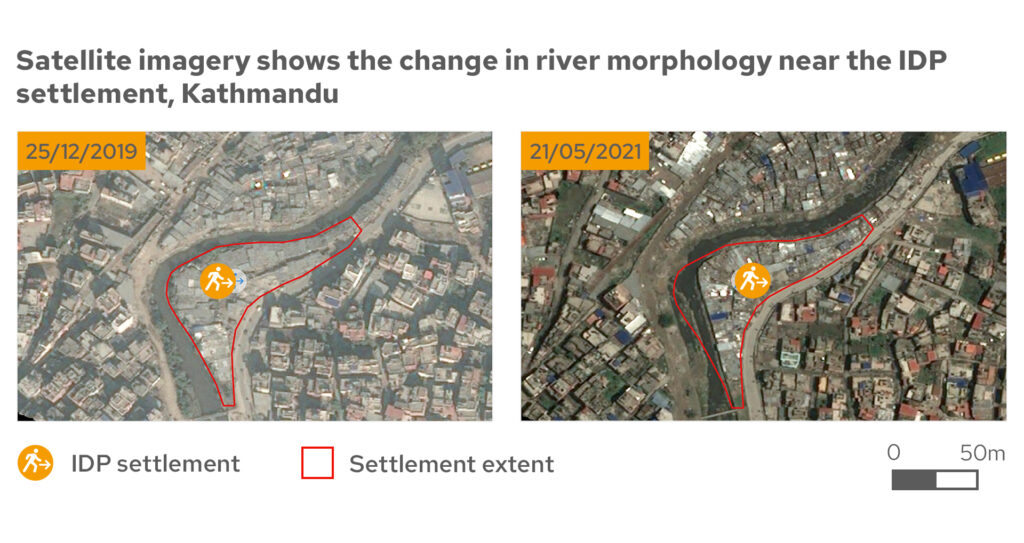

Mapping shows displaced persons living in vulnerable environments that only increase in their level of risk over time. The following maps highlight a displaced population in Kathmandu, Nepal. Over time, the population density and information dwellings increase alongside the river, and the site itself does not protect from the threat of disasters.

Hazards faced by people living in informal settlements

In March 2021, one third of those living in this informal settlement felt that their biggest risk was flash floods. Unfortunately, in September 2021 this risk was realised when 85 households felt the devastating effect of approximately 105mm of rainfall within three hours. This resulted in a flash flood in the Bagmati River. Water entered their settlement through the weep holes and construction joints on the embankment wall, with further water running off the adjacent road submerging the settlement. CSO staff commented, “They told us flash flooding was a risk during the VFL Lite survey but no one imagined it could happen to the extent in which it did.”

“There is an exodus of people from the desert and desert villages of southern Morocco due to drought, but also educational institutions of all kinds, such as universities and schools, and health services are not functioning as well as they are in cities. There is unemployment so people keep moving.”

GNDR member in Morocco

Impact of Covid-19 in urban areas

Finally, desk research highlighted the effect of the Covid-19 pandemic on displaced communities in urban areas. Not only are they more likely to contract the disease due to over-crowded living spaces, often without good water and sanitation infrastructure, the threat was compounded by their lack of access to basic health services. Furthermore, “The Covid-19 pandemic has compounded a pre-existing culture of distrust, xenophobia and intolerance towards minorities, including migrants. This aggravates migrants’ feelings of isolation and overall leads to further exclusion – in multiple dimensions – from the rest of society.”

Global Finding 2: Economic insecurity

Next chapterForced Displacement Global Paper

ContentsCredits

Main photo: Jowle camp for displaced people, Garowe, Somalia. Credit: EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid

Pie chart: Community-level data from our Making Displacement Safer programme.

Map: Produced by MapAction. Created: 07/07/2021. This map uses Pleiades satellite imagery to identify the change in morphology of the Bagmati River and the increasing pressure it is putting on the IDP settlement. Supported by the Bureau of Humanitarian Assistance. Data sources: NSET, AIRBUS DS GEO. The depiction and use of boundaries, names and associated data shown here do not imply endorsement or acceptance by MapAction or GNDR.

Project funded by

United States Agency for International Development

Our Making Displacement Safer project is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) – Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance. Content related to this project on our website was made possible by the support of the USAID. All content is the sole responsibility of GNDR and does not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID.

Visit their websiteBecome a member

Membership is free and open to all civil society organisations that work in disaster risk reduction or have an interest in strengthening the resilience of communities.

Join GNDR