FORCED DISPLACEMENT

Finding 5: Responses not localised

Effective localised response is not yet the norm for addressing complex disasters.

Whilst global trends have emerged from our analysis, it is clear that the multiple and complex causes and consequences of displacement call for a localised response.

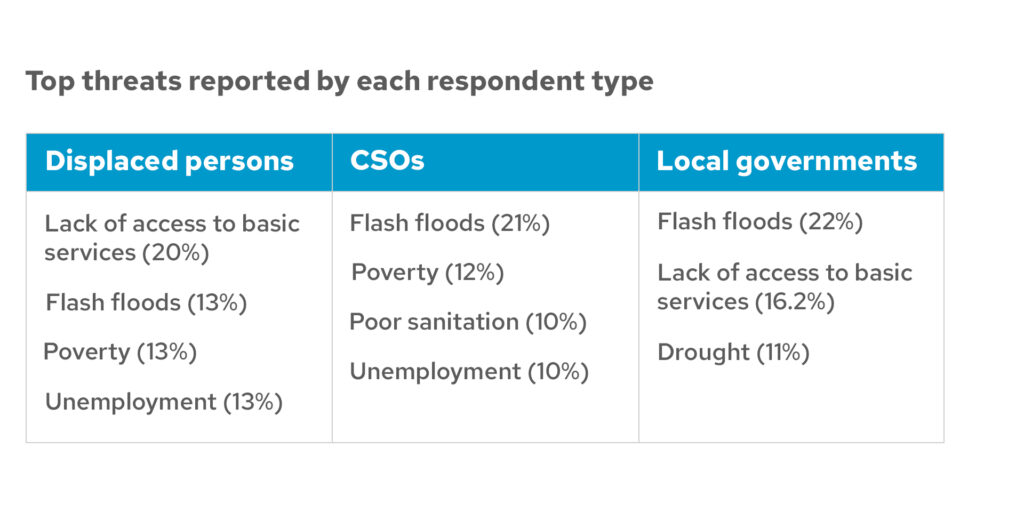

VFL shows that individual country findings to perceived threats are all quite different. This is an indication that response to disaster risk reduction of the displaced needs to take into account local contexts. For example, five years after relocation from a tsunami has left displaced persons in Sri Lanka concerned about poverty (24%), alcoholism (14%) and poor sanitation facilities. Climate change in the Republic of Congo has left displaced persons concerned about flash floods (31%), epidemics (25%) and a lack of access to basic services (9%). Conflict in Iraq has left displaced persons concerned about poverty (32%), unemployment (23%) and a high cost of living (17%).

Story analysis found over 530 different challenges from 185 communities in 60 countries. From systematic discrimination and violence towards the Rohingya people fleeing Myanmar to winter flooding in Lebanon; from the creation of protected rural areas in Brazil to urban redevelopment forcing people from their homes in Los Angeles, United States of America the multi-dimensional triggers and consequences connected to displacement risks that GNDR member shared were vast.

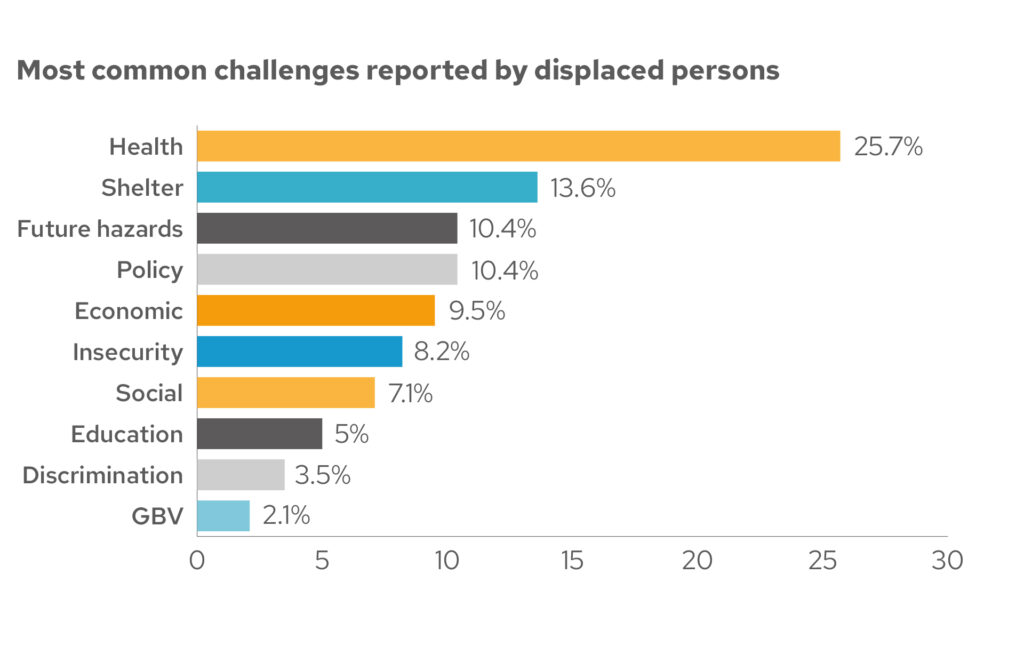

Similarly, continued challenges faced by the displaced populations varied from our global story analysis. 26% of challenges were related to health, 15% related to housing and shelter, 10% related to economic concerns and future hazards, and 8% related to ongoing security issues.

Effective local governance mechanisms are needed

In all of this contextual difference, there is a difference of opinion between local governments, civil society groups and displaced communities. Whilst this is expected as the stakeholders play different roles, as far as possible, CSOs and government need to align to the perspectives of the displaced.

Gaps in local governance structures

A clear gap in local governance structures has emerged with the majority of responses highlighting that effective local governance mechanisms are not in place to address emerging challenges. When only looking at perspectives of local government representatives the majority of responses are:

- Displaced persons are rarely consulted in the design of policies, plans and activities to reduce disaster risks

- Displaced persons are not at all given access to the financial resources they need to reduce risks

- Displaced persons rarely have access to timely and usable information to help them reduce the risks they face

Corruption and a lack of transparency is a significant issue with 14% of respondents to VFL highlighting that it is the biggest barrier to taking actions to address risks faced. This is followed by a lack of facilities, resources and communication in place which, ideally, should be coordinated by the local, if not national, government.

“In 2018, Ethiopia recorded the third highest number of new displacements worldwide, with 3,191,000 internally displaced persons. Mainly triggered by ethnic and border-based conflict, several population groups already at increased risk of gender-based violence will be more gravely impacted. Adolescent girls, especially, face particular risks resulting in increased domestic responsibilities keeping them in the home, discouraging school attendance and increasing the risk of early marriage. Combined, this results in a lack of understanding on health, education, rights and services, thus leaving them with limited access to these services. Many essential facilities are not located in areas that are safe and easily accessible to women and girls. Women, girls, boys and men who are all survivors of violence, face social discrimination and exclusion and are at risk of secondary violence as result of the primary violence.”

GNDR member in Ethiopia

Lack of financial resources to deal with the challenges

Budget and allocation of resources has been cited by CSOs as a common problem. “Even when resources are available, they don’t reach the people in need and get ‘lost’ in the process.” It must be noted that this finding does not point specifically to local governments as being corrupt because other stakeholders in different contexts might be exploiting resources intended for displaced persons. However, what is interesting is that local governments themselves recognise the challenges. They too highlight the same factors which are the biggest barriers to address the risks faced by the displaced communities. Further, in Niger CSOs have stated that, “There is political will from the government side to support displaced populations and help build their resilience, but financial resources are lacking. There is a good structure at national level for dealing with displacement issues but it is not implemented as the central government does not have the budget to deliver the policy.”

Global Finding 6: Exclusion from decisions

Next chapterForced Displacement Global Paper

ContentsCredits

Main photo: Carting pots to the kiln even if the road is flooded. Near Bagan, Myanmar. Credit: Deanne Scanlan on Unsplash.

Pie chart: Community-level data from our Making Displacement Safer programme.

Project funded by

United States Agency for International Development

Our Making Displacement Safer project is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) – Bureau for Humanitarian Assistance. Content related to this project on our website was made possible by the support of the USAID. All content is the sole responsibility of GNDR and does not necessarily reflect the views of the USAID.

Visit their websiteBecome a member

Membership is free and open to all civil society organisations that work in disaster risk reduction or have an interest in strengthening the resilience of communities.

Join GNDR